Originally housing for Nigeria’s upper class, these homes have become overcrowded tenements, often in disrepair. Could the architectural style still offer lessons to a rapidly urbanizing city?

With new office towers, shopping malls and even entire neighborhoods sprouting up to accommodate a growing population, Lagos, Nigeria, has welcomed an array of architectural styles. But there is one traditional housing type that shows the many transformations the city has undergone in becoming West Africa’s largest metro area.

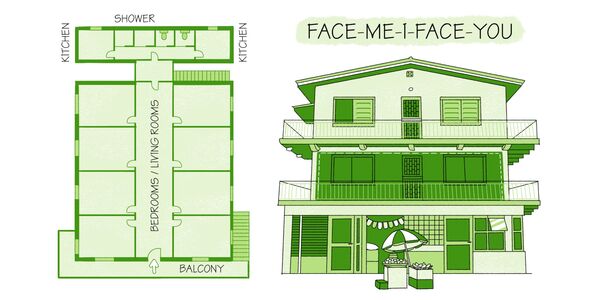

It’s a tenement whose vivid name expresses many residents’ love/hate relationship with it: the Face-Me-I-Face-You. Typically a one- or two-story house with rooms grouped around a gloomy central lobby, the structure features rooms whose doors face one another across an axial corridor— so that the first thing neighbors leaving in the morning see is each other. Found in Lagos’ core right to the outskirts of the city, these buildings were originally intended as individual houses for large families; today most are tenements for mixed groups of low-income renters, with shared kitchens and bathrooms in a separate service building behind the main house.

With both a lack of privacy and often poor living conditions, the housing type now has a reputation for mistrust among tenants. This, however, was not always the case. In mid-20th-century Lagos, the Face-Me-I-Face-Yous were seen as a suitable solution for the rapidly expanding city, introducing modern architecture and acting as a catalyst for change in Nigerian society. And with widespread renovation and rethinking, these buildings and their complex history might still offer inspiration for Lagos’ future.

An Afro-Brazilian Fusion

Buildings with enclosed central corridors like the Face-Me-I-Face Yous are not traditional in Nigerian residential architecture, where compound houses (found across West Africa) were the staple until the mid-19th century. These large houses with rooms facing a central courtyard embraced the culture of communality — extended, and often polygamous, families lived together, with the home opening its arms to the community.

From the 1850s to the 1920s, this traditional home type was reshaped by the return of ex-slaves from Brazil. These were mainly people of Yoruba heritage — an ethnic group that already predominated in the Lagos region — who brought a Brazilian housing style and a particularly high standard of building construction. This housing style entailed one- or two-story stuccoed buildings (sobrados) with a linear layout inside and plaster ornamentations on the exterior.

The Brazilian houses of Lagos were forerunners of the Face-Me-I-Face-You. They also influenced the conversation around communal traditions, which were shifting focus away from communality towards individualism at the time. As Christianity grew as an alternative to the traditional religion, people began to forgo polygamous marriage. Older family structures, which involved a man with multiple wives, gave way to smaller nuclear families with a man, one wife and their children; these created residential patterns that the very large spaces of compound houses could not accommodate.

To create more private spaces, the courtyard common to compound houses was replaced by a central indoor lobby resembling the floor plan of Brazilian houses. Without a courtyard to host daily communal activities such as cooking and clothes washing, daily chores were relocated to a small service building at the back of the house, which contained a kitchen, toilet, laundry and bathing facilities, served from 1915 onwards by a main water system. While this new housing type removed the courtyard, the plan was otherwise quite similar to the compound houses, with each individual room opening onto the corridor rather than inter-connecting. Within this basic template there were many variations — some had shared common rooms for welcoming guests, others had balconies, or combined the service building with the main house.

A Middle-Class Boom

By the 1950s and ’60s, these houses had spread from the elite to the middle class. Simpler, more modest one-story forms emerged, while still retaining the typical layout of a central lobby flanked with facing rooms on either side. During this period, when the homes were still occupied by extended families (albeit ones with a single husband and wife at their heart), the typical layout would consist of a living room, dining room and four to six bedrooms, which were usually equally sized.

The houses were a perfect fit for the new smaller family sizes. A fast-growing Lagos — Nigeria’s capital until 1976 — attracted migrants from across the country, and these buildings were easy to construct and relatively affordable.

Not all of their characteristics were greeted with equal enthusiasm. For people used to living in compound houses, nostalgia for the old central courtyards made them feel they needed to connect their homes to public space in ways that the inward-facing plan lacked. Thus the classic building plan adopted large balconies and verandas that wrapped the structure on multiple sides, a feature of British colonial structures. Many were capped with beautiful railing designs, some with calligraphy of motifs personalized to families who owned the homes.

These balconies gave the Face-Me-I-Face You a renewed outdoor focus for family life and a much-missed sense of community spirit. Spacious balconies created an extension of the house to the street, enabling communication, transparency and interaction between buildings and people. They also helped adapt the buildings to a feature of Yoruba culture: grandiose parties welcoming everyone that are called “owambes” — a Yoruba word that means “it is there.” (The party is implied.)

Without access to the compound house courtyards that used to accommodate these parties, Lagosians improvised by erecting tent-like structures locally called “canopies” on the roads adjacent to the celebrant’s house, which immediately activate the street with music, dance and energy. The external balconies of Face-Me-I-Face-You houses interact well with this culture, drawing people out of their rooms to join the celebrations and creating a communal gaiety. Such is the suitability of this layout for public celebrations that merge homes with the street that the spread of external balconies has also helped to spread this street party culture around the country.

The International Style Arrives

The 1980s saw a change in residential architectural fashion, as the city’s upper class moved to modernist buildings, an international style that had been gradually taking root in Nigeria since the 1950s. These new homes suited contemporary ideas about ideal living conditions: They offered more fully integrated floor plans, where rooms of various sizes connected to each other, rather than just to the lobby, and bathrooms were close by, rather than in a separate wing of the house.

As this style became the new symbol of the wealthy, the lower classes replaced them as tenants in the Face-Me-I-Face-Yous. This association with less-affluent tenants was reinforced by the government, who used the Face-Me-I-Face-You-style layout in buildings constructed as government-sponsored affordable housing, notably during the period of the Second Republic from 1979-1983, when mass housing units were developed to address to the growing city’s housing deficit.

This slide down the social prestige scale saw the trend for breaking up Face-Me-I-Face-You houses into smaller units from the 1990s onwards, in a transition from family houses to tenement housing schemes. Developers and owners rented individual rooms as units, implemented informal tenancies and overcrowded the buildings.

In time, the Face-Me-I-Face-Yous came to reflect the rapid, unequal urbanization experienced across Lagos as a whole. They became homes to diverse ethnic groups from around the country migrating to Lagos, leaving tenants previously unfamiliar with each other in a state of social tension, in apparent competition for a better standard of living. With the larger extended families the buildings were intended for long since departed, a diverse, non-related population risked making Face-Me-I-Face-Yous places of conflict.

The lively daily friction of living in this way has made the complexes a common setting for Nigerian drama and comedy, as places where both the charming and frustrating aspects of living in close quarters with sometimes larger-than-life neighbors are clearly exposed. These constant tensions have also earned the buildings another tongue-in-cheek name: the Face-Me-I-Slap-You.

And yet, while this type of housing is now often overcrowded and in poor condition, it still offers some advantages that aren’t found in contemporary housing. The broad, spacious balconies of older Face-Me-I-Face-Yous offer possibilities for a vibrant public life — not just owambes but daily street leisure and house-to-house conversations. These are absent from many contemporary Nigerian houses, which have small balconies that can’t truly extend interior spaces and often have high fence walls that keep them isolated.

In turn, current houses and apartment buildings also develop an inward-looking character, making the contemporary street a quiet gallery of fence walls. Face-Me-I-Face-You houses may mostly lie in a poor state today, but they once possessed powerful design ideals, starting a dialogue on what Nigerian architecture was, and what it might become. This dialogue could still inspire a renovation and rethink of surviving homes — and a source of future inspiration for building anew in Lagos’ dense urban fabric.

Source : Bloomberg